A Journey to Babylon: The Ancient City That Defined Modern Civilization

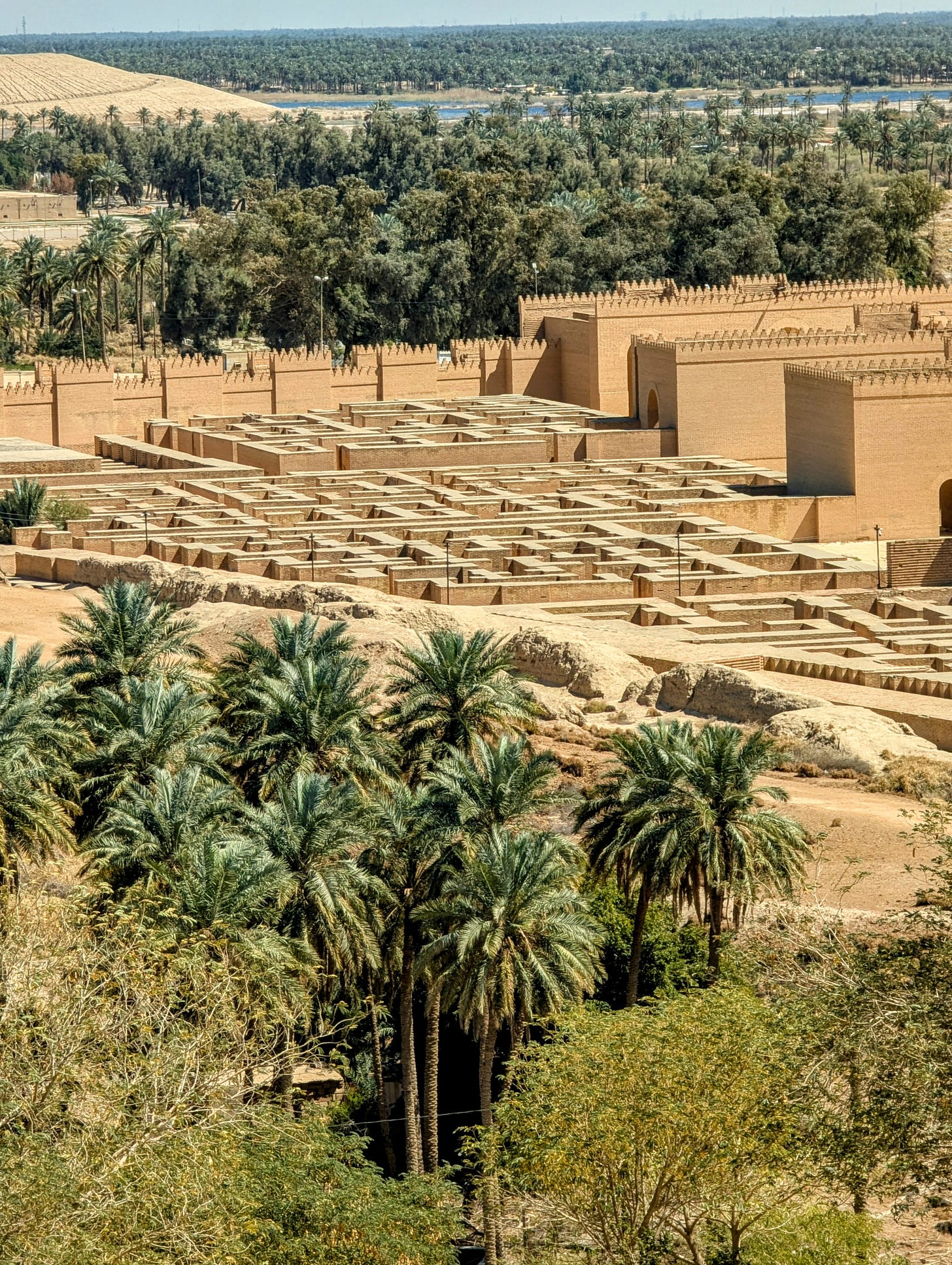

The largest city of the ancient world, and the first to reach a population of 200,000, now an archeological site that I had all to myself

📍 Babylon, Hillah, Iraq

Few historical epochs evoke as much marvel, mystery, and myth as Babylon, the first city in the world to surpass a population of 200,000. Babylon wasn’t just the largest metropolis of the ancient world; it redefined what a city was capable of. Civilization as we know it — culture, commerce, and governance of modern scale — began here.

And yet, when I visited, I was the only one there.

Even before the fabled rise of Babylon, the fertile plains of Mesopotamia hosted humanity's first experiments in settled life. By the third millennium B.C., the Sumerians had taken the revolutionary step of organizing their once-nomadic existence into Uruk, the first city ever built. A thousand years later, the Babylonians built upon this foundation with transformative ambition, redefining what a city could achieve.

To administer a city as vast as Babylon required more than just brute force; it necessitated record-keeping, contracts, bureaucracy. And so, cuneiform, the world’s earliest form of writing, was popularized — not to tell stories, but to track trade, taxes, and treaties. Babylon’s power didn’t just rest on its walls or its armies, but in the most modern form of authority: data.

The first time I saw cuneiform in person, it felt shockingly casual, almost irreverent. Scattered bricks in the dirt, script worn but still legible — possible legal codes, astronomical calculations, administrative records, and other precedence-setting human thought. These nearly accidental finds were among human’s earliest attempts to defy ephemerality, to literally set knowledge in stone. The unattended bricks were where the human impulse to document, to codify, to make sense of the world in symbols first reached mass scale. If Babylon teaches us anything, it’s that data, not just swords, determines the legacy of civilizations.

Babylonian King Hammurabi understood this well. In the 18th century BCE, he unified much of Mesopotamia and etched the first comprehensive written legal code into stone (found on basalt slabs housed in the Louvre). The world's first truly complex society required a legal framework, and from this need emerged Hammurabi's justice, the principle of "an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth." Standing in Babylon's stark emptiness, the weight of its precedence felt almost ironic. The world's first great city is now a place where no one lives, yet we are all heirs of its foundational legacies — obeying laws, participating in economies, and relying on a system we didn’t personally create.

Babylon wasn’t just bureaucracy — it was myth, marvel, and ambition. The Hanging Gardens, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, were said to be here, with suspended greenery that defied the desert. Their existence is debated, but does it matter? Babylon’s real wonder was its power to mold civilization equally through reality and myth.

In Babylon, I felt the rhythm of humanity. Even time itself is a Babylonian invention: the division of hours into 60 minutes, of minutes into 60 seconds (known as the “Sexagesimal System”). Babylon was also where the first astronomers mapped the heavens, predicting celestial events with a precision that defied their rudimentary instruments. But their science wasn’t separate from faith — it was divination, a means of decoding the will of the gods. Unlike today’s rigid divide between science and religion, for Babylonians, knowledge was sacred, and the two were inseparable.

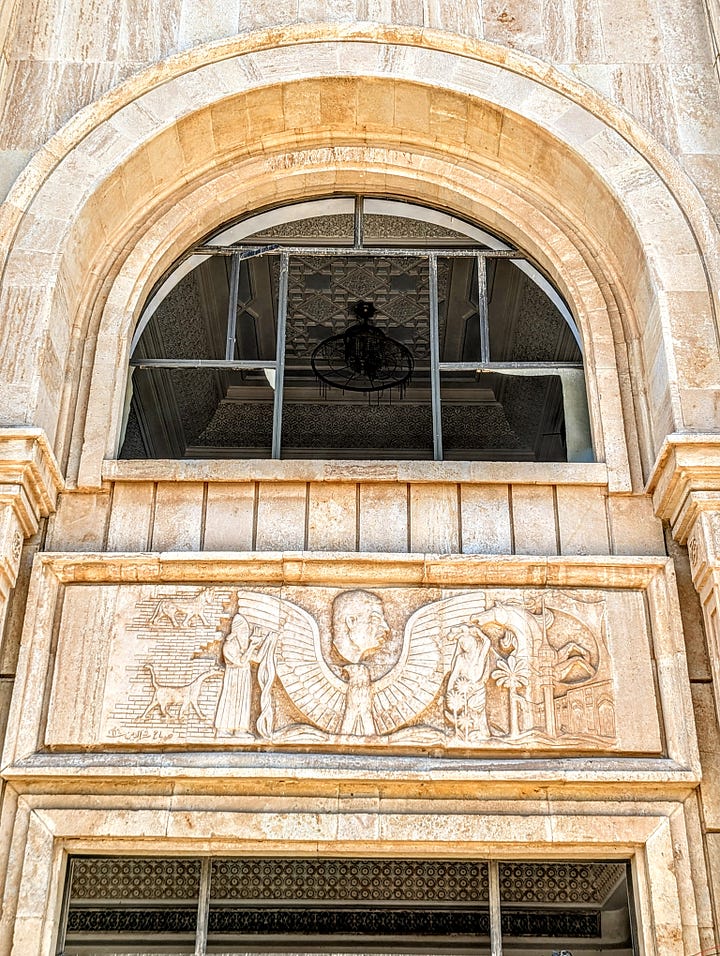

Babylon's most famous king, Nebuchadnezzar II, wasn't just building an empire; he was crafting its enduring myth. He understood that true legacy transcended mere territorial control, residing instead in the power of symbols. His grand avenues, towering temples, and impregnable walls weren't simply feats of engineering; they were deliberate acts of branding, designed to make Babylon a lasting legend.

And it worked: Millennia later, another strongman, Saddam Hussein, tried to graft his own authority onto Nebuchadnezzar's legacy by stamping his name onto the very bricks of the ruined ancient palace. Perched over the ruins, Saddam’s palace is an opulent ghost — five-story doors opening onto boastful ballrooms, frescoes peeling in the desert heat, latticework that bears his signature. The tyrant wanted a piece of Nebuchadnezzar’s legacy, but history had other plans.

Babylon, for all its might, proved mortal. Cyrus the Great’s arrival in 539 BCE began a long decline through conquest, abandonment, and the desert's slow creep. Yet, to declare Babylon truly vanished misses the point. Even in ruin, its influence lives on, not just as an archaeological dig, but as a historical template. Walking its main thoroughfare, I imagined its diversity — Akkadian officials, Aramaic traders, Sumerian traditions influencing temple rites. Babylon’s strength wasn't in forced uniformity, but in managed order. It absorbed rather than erased, funding even foreign temples with the same taxes that supported its own Marduk. This forgotten lesson in governance, of inclusive administration, remains relevant in today’s world.

However, for some, Babylon holds a somber place in history as a city of exile. When Nebuchadnezzar’s armies sacked Jerusalem in 586 BCE, the Judean elite were marched here in captivity (“By the rivers of Babylon, there we sat down, yea, we wept, when we remembered Zion”, Psalm 137:1). But in the sorrow of forced displacement, the Judeans, my ancestors, underwent an enduring transformation. Their religion, Judaism, evolved from faith centered on a single holy temple to one centered on texts and traditions that were not bound to a particular geography. Centuries later, the Talmud, written in Babylon, would shape modern Jewish life more than the Jerusalem Temple ever had. Standing in Babylon felt both foreign and familiar: yes, it was exile, but it was also the birthplace of rabbinic Judaism and the traditions that defined my modern upbringing.

Babylon evoked a different kind of “wow” than other archaeological sites. Though perhaps the oldest place I've visited, it felt surprisingly immediate, a point of connection, almost elemental. Here, I sensed the very beginnings of that fundamental human state of living within a civilization. In that sense, Babylon isn't a lost city; its essence persists within us. We are all, in a way, Babylonians.