A Tale of Two Belfasts: Crossing The Largest Divided City in the Western World

The haunting legacy of the Irish Troubles (1968-1998) showed me that bullets don't just travel through distance; they also travel through time

📍 Belfast, Northern Ireland

The Divis Tower of Belfast rises over Falls Road, bearing unhealed scars from troubled times. From this residential tower, once a former battleground, I would be guided by two men who fought on opposite sides of Northern Ireland’s 30-year conflict, known as the Troubles — a violent struggle that lasted from the late 1960s until the 1998 Good Friday Agreement. One guide, a former volunteer for the Irish Republican Army (IRA) — a political and terrorist organization that used violence to pursue the unification of Ireland and end British rule in Northern Ireland — would lead me through his own embattled West Belfast. The other, an Ulster Protestant who fought to keep Northern Ireland part of the United Kingdom, would guide me through his adjacent neighborhood. Their stories were not just accounts of past “Troubles”; the scars remain in unforgiving murals, pained memorials, and reinforced walls that make Belfast, quite literally, the largest physically divided city in the Western world.

The ex-IRA guide set the tone: this dual narrative, he said, was “a story that ends better, but doesn’t end well.” He added, “Bullets don’t just travel through distance; they travel through time.” Gates that once stayed open until midnight between Catholic and Protestant neighborhoods now close at 7 p.m. There are two police stations, two libraries, and two segregated schools—all within blocks of each other, each serving its respective divided community. The walls have grown higher since the Troubles—three times higher, in fact. With little real integration, another generation is growing up in a tormented time warp.

The walls themselves have a hauntingly ironic name: “peace walls.” More than 100 such barriers exist, and they stretch for miles, separating Catholic nationalist and Protestant loyalist communities. These walls did not exist before 1969, the year the Troubles erupted. But the conflict rewrote Belfast’s landscape, carving out physical and psychological divides that seem as impenetrable today as they did decades ago.

The ex-IRA guide’s story began at Divis Tower. This 1960s apartment building became a frontline during the Troubles, when British soldiers took over its top floors to surveil the IRA below. Today, the British soldiers are gone, but the scars of what my guide called an “occupation” remain. “Occupation,” or perceived occupation, depending on who you ask, is a connection that links Irish nationalists to the Palestinian cause. At Divis Tower and the surrounding neighborhood, I saw more Palestinian flags than Irish ones, signaling a visceral solidarity that transcends geography. For these Irish Catholics, continued British rule is a last vestige of colonization — the same force that once stripped them of their culture (England’s Queen Elizabeth I ordered all harps, now a symbol of Ireland, to be destroyed on punishment of death), language (indigenous Gaelic was nearly eradicated by enforced English), and worst of all, dignity.

The parallels to Israel’s occupation of Palestinian territories resonated deeply for my ex-IRA guide. In the aftermath of the October 7 War, the flags, murals, and memorials became even more numerous. This solidarity is not merely symbolic: during the Troubles, the IRA trained with the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO), seeing their struggle as a mirror of their own fight for self-determination in what they considered a colonized land.

As we crossed the gate separating Falls Road from Shankill Road, we entered Protestant loyalist territory. Here, the Union Jack flies proudly, and murals of British soldiers and loyalist paramilitaries cover the walls. My Protestant guide took over, as my ex-IRA guide turned back. He was unwelcome here: The IRA was responsible for the deaths of over 1,800 people, including approximately 600 civilians, during the Troubles.

“The root of all conflicts is dehumanization,” the loyalist guide began. He asked how it could be that the same Protestant and Irish Catholic soldiers who fought together in the First and Second World Wars turned their weapons on each other only 20 years later. He teared up at a mural depicting the Battle of the Somme, a battle in which Irish Catholic and Protestant soldiers honorably served together in the British Army during World War I, shaking his head in disbelief.

“We were fixated on who was first-class and who was second-class citizens. But we were all third-class citizens and didn’t realize it.” And still today, all sides are losing. Institutionalized separation means the next generation is growing up with the same entrenched identities, the same “us” or “them” existence. Indeed, the status quo is better than the previous “us” versus “them” conflict, but the absence of bullets doesn’t mean the presence of peace. In Belfast, the conflict has outlived its combatants, entrenched in walls of concrete and fear. In this doom loop, the past refuses to release its grip on the present.

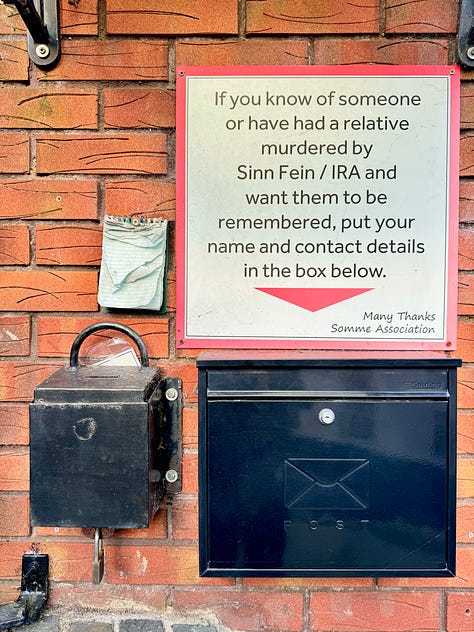

For my loyalist guide, the chief grievance is that Sinn Féin, once the political wing of the IRA, is now the largest political party in both Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. Many of the party’s leaders are former IRA members who once took up arms in a violent struggle against British rule. Their rise to legitimate political power signals both progress and unresolved tensions. To the loyalist guide, what may appear as reconciliation feels like a bitter pill to swallow. Neither forgiven nor forgotten on their side of the “peace wall,” their anger toward Sinn Féin remains, channeled into murals and memorials rather than munitions.

Nearly three decades have passed since the Good Friday Agreement officially ended the Troubles. But my tour made it painfully clear that while the active conflict may be over, nearly everything that caused it remains. The walls are higher, the gates close earlier, and the community remains as divided as ever. The past’s scars leave the present wounded, albeit no longer actively bleeding. Both guides agreed: the decades-long ceasefire is an extraordinary achievement, but it has become a crutch to avoid resolving the tinder box of pain. Peace, as it turns out, is more than just the absence of war.

It’s very interesting to see your perspective.

A point I’d make is that your loyalist guide didn’t seem to know why The Troubles happened.

After WW1 and partition, Northern Ireland experienced 50 years apartheid enforced by a fascist government which legalised discrimination against catholics and genuinely treated them as second class citizens both in legislation and practice.

The inevitable civil rights movement in the 60s produced no significant results as peaceful protesters were regularly attacked and even murdered by both state and paramilitary forces.

That history is the progenitor of the troubles and is testament to what happens when peaceful protest against oppression is suppressed.

Loyalist paramilitaries weren’t simply fighting to retain their place in the uk; that was never really in doubt. They were fighting to maintain their position of supremacy.