Inside the World's Largest Cryonics Facility, Where Death May Be Just a Pause

In the heart of the Arizona desert, a non-profit holds the frozen dreams of hundreds who refuse to accept the finality of death.

📍 Scottsdale, Arizona, USA

The Ice-Cold Dreams of Alcor

In sun-baked Scottsdale, Arizona, nestled amongst golf courses and retirement communities, lies an organization dedicated to an audacious proposition: defying death. Alcor Life Extension Foundation, the world's largest cryonics facility, is a testament to humanity's enduring hope of conquering mortality.

For skeptics, cryonics might resemble a luxurious form of denial – a last-ditch effort by the well-heeled to outrun the grim reaper. It involves the freezing of dead people who cling to the fantastical notion that future civilizations will possess the technology to revive them. The optimism of cryonics enthusiasts can take on an almost spiritual fervor, where the promise of future science holds sway over the constraints of present-day knowledge.

But cryonics believers have a different story. For them, it's not about resurrecting the dead; it's about saving the gravely ill. They don't deal in corpses but in 'patients' awaiting a cure that simply doesn't exist yet. Today's terminal case could very well be tomorrow's routine medical miracle. Cryonics, the logic goes, is an extension of emergency medicine; it's buying time until science catches up.

The problem is that reviving a cryonically frozen individual is, at present, impossible. Legally, it isn't even considered a medical procedure—it's more like a bizarre form of burial. Freezing someone who hasn't been declared dead is tantamount to “homocide” by law. And sadly, even if you have a terminal illness and wish to be preserved before further bodily deterioration, current laws won't allow it.

This is where the cryonicists' peculiar definition of death comes in. They argue that death is not an event but a process. The law might see it as a binary—you're either alive or dead—but for a cryonicist, things aren't so simple. With the help of a Do Not Resuscitate (DNR) order, a cryonics team can start the preservation process immediately after cardiac arrest, well before brain damage sets in. It's a race against time: from hospice, the fatal accident, or the chance medical episode to the doorstep of Alcor, in an attempt to outrun conventional mortality.

The father of this movement against mortality was Robert Ettinger. Initially a science fiction aficionado, he envisioned a world where sickness was eradicated and death became a voluntary choice. But after decades, the harsh realities of illness and aging caught up with him. As a physics professor, he then began pondering the possibility of circumventing death entirely. He contemplated his own preservation through freezing, with the expectation that he'd one day be revived with the tools to restore his health. Ettinger's 1962 book, "The Prospect of Immortality," kickstarted the cryonics movement.

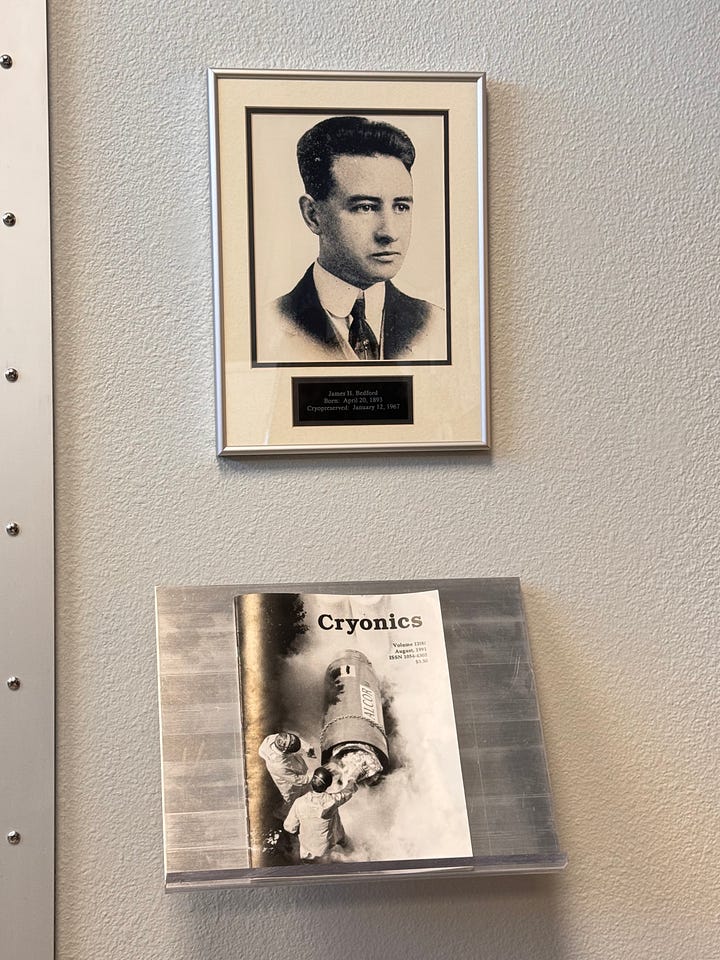

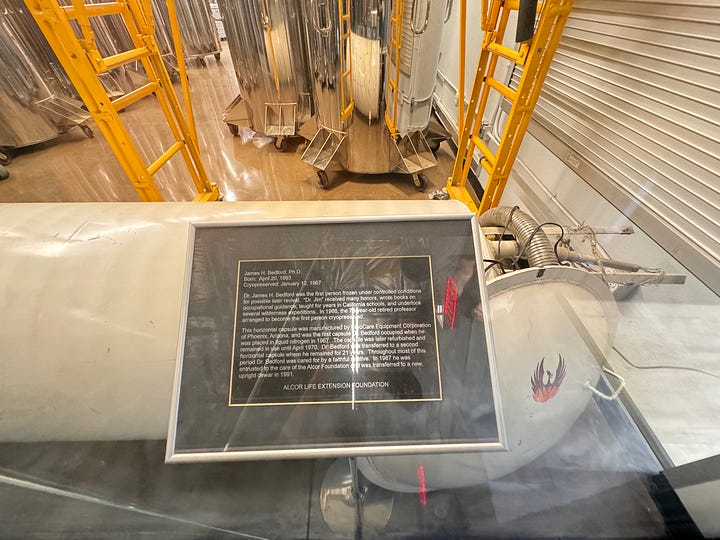

James Bedford, a psychology professor dying of cancer at the age of 73, was the brave pioneer who became the first to cyropreserve himself in 1967. Over three hundred individuals followed Bedford and now lie in a state of frozen repose, their bodies entrusted to the ambitious (and some might say outlandish) promises of cryonics. Alcor, the largest among the facilities where they lie, boasts around a thousand 'members' who aspire to one day rejoin the land of the living.

The price tag isn't cheap: Alcor's yearly membership fee hovers around $700 (15x the prospective ‘patient’s’ age), while transport, preservation, and the promise of revival incur a $220,000 cost. For those on a tighter budget, the option of just freezing your brain (called “neurocryopreservation”) cuts the cost down to $80,000. Alcor, in an attempt to distance itself from the less reputable cryonics companies of the 1970s that ultimately went bankrupt, allocates a hefty chunk of these fees to a Patient Care Trust – essentially an insurance policy to ensure that their clients won't thaw out due to financial challenges.

Alcor isn't merely a human popsicle warehouse. It conducts research into cryopreservation—the underlying science of storing biological tissues at ultra-low temperatures—which has significant applications in fields like emergency medicine, long-distance space travel, and organ banking. This is one instance where those audacious dreams of resurrection might benefit the living. Cryonics places immense faith in human optimism: that bodies can be held in stasis indefinitely, and that Alcor itself will endure for centuries – even millennia – until the technology to fulfill its members' revival wishes is finally realized.

Inside the House of Frozen Dreams

Alcor's Deployment and Recovery Teams are a curious mix: trained medical professionals, first responders, and hardened military veterans stand ready to stabilize, preserve, and transport the newly deceased to Alcor's Scottsdale headquarters for long-term storage. The process is meticulously documented: a 'death contract' formalizing your desire for preservation (head or whole body), and a 'revival contract' laying out the terms of your eventual return—age, health status, even the possibility of being reanimated as an artificial intelligence. Life insurance policies are the usual means of financing this futuristic gamble.

There are two membership tiers at Alcor: “Members” are those who wish to be cryopreserved but lack the financial means currently, and “Cryopreservation Members,” who have their death wish prepaid, revival contract signed, and are ready to enter the deep freeze. The latter wear dog tags and bracelets with instructions on minimizing tissue damage until the Recovery Team arrives—the most urgent directive being to submerge their bodies in ice-cold water before being transferred to Alcor's liquid nitrogen 'dewars' for long-term storage. Think of it as the low-tech prelude to a sci-fi odyssey.

Walt Disney's frozen slumber might be an urban legend, but Alcor won't confirm or deny that it stores other celebrity patients. Stepping inside the facility, however, one is confronted by the very real faces of those who've made the cryonic choice: portraits of 'patients' line the hallways, giving names and faces to the fantastical hopes harbored within. This isn't treated as a morbid joke, but as a venture fueled by relentless optimism in the unstoppable march of scientific progress. The youngest patient is a 5-year-old girl from Thailand, while the oldest were cryopreserved in the 1970s. Each portrait includes a date of birth and cryopreservation—death dates are irrelevant, as revival could render dying a temporary inconvenience.

Alcor takes its contracts very seriously. Witnessing the signing of a new member's paperwork is a somber affair. Each member requires two non-family witnesses to sign the contracts, and a notarized document confirms that your remains will indeed be handed over to Alcor upon death.

The central argument for cryonics rests on our evolving understanding of death. Today, 'dead' typically means cessation of cardiac activity for 4-6 minutes—the amount of time the brain can survive without oxygen before irreversible damage occurs. Alcor contends in its Science FAQ that the brain doesn't immediately cease functioning after this interval; rather, a cascade of detrimental processes condemns it to destruction over hours. Techniques like cooling the body instead of warming it after circulation stops, reopening blood vessels, and drug therapies could prevent this. Cryonicists point out that experimental procedures are already extending the amount of time someone can survive warm cardiac arrest without brain injury beyond ten minutes. They believe that future, more sophisticated technologies could stretch this window well past an hour – rendering our current notions of death obsolete.

In other words, what we deem as 'dead' might more accurately be phrased as 'doomed under present circumstances.' A 1950s cardiac arrest victim wasn't dead; they lacked the treatment necessary for survival. Today, we possess that treatment. Therefore, someone who 'dies' today from cardiac arrest isn't truly dead, but merely lacks the tools future medicine might provide.

Vitrification and Long-Term Care

A tour of Alcor demonstrates the full arc of the cryonics process. After pick-up, newly deceased members are plunged into an ice bath and flown to Scottsdale Airport, just across from Alcor. Next comes a process known as vitrification. It's here that the real divergence from conventional freezing occurs. If you were to simply freeze a human body, the water inside its cells would form ice crystals, causing irreparable damage—essentially turning tissues into mush. Cryonics technicians avoid this by completely replacing the blood with a medical-grade antifreeze solution. Once the body's temperature is reduced, it becomes a glass-like substance—liquid molecules slowing to a standstill—and biological time freezes.

Finally, you are ready for 'long-term care'—immersion in a towering ten-foot tall thermos filled with liquid nitrogen. Up to three other members reside in this upright container, each in a separate quadrant. Neurocryopreservation members get a smaller 'dewar' shared with around 45 other brains. Storage is intentionally upside-down, as liquid nitrogen gradually boils off from the top of the tank.

The entire storage process is remarkably low-tech. No electricity is involved—the dewars function like giant thermoses, keeping the contents perpetually chilled. Blackouts pose no threat, and the only real maintenance is the occasional topping-off of nitrogen. It's this simplicity and stability that lend a sense (however faint) of plausibility to Alcor's ambitious promises.

Cryonics may be an unorthodox gamble, but it's a strangely moving one. It's a testament to the undying human desire to hold on, even when faced with the seemingly impossible. Whether it's pure hubris or an audacious form of hope, Alcor promises its members a second chance. And like most things born from both science and dreams, the truth might lie somewhere in between.