If the Lorax Ruled a Country: How Bhutan Became the First and Most Carbon-Negative Country in the World

Bhutan is a literal breath of fresh air and blueprint for sustainability in a world that desperately needs one.

📍 Bhutan

Bhutan is a kingdom of anomalies, as one of the few places that embraces modernity without being spoiled by it. This tiny Himalayan nation takes what it wants from the 21st century but doesn't let the gilded promises of globalization compromise its soul. From the moment I touched down in Paro—known for having the world's most challenging airport landing, a heart-stopping descent between mountain peaks—I could see and smell that Bhutan was unlike anywhere else. As the first and most carbon-negative country in the world, this kingdom of fewer than a million people removes more carbon from the atmosphere than entire countries emit.

I previously wrote about how Gabon became the second-most carbon-negative country in the world. This resulted from a national commitment to protecting its forests, which is credited with making Gabon home to the largest population of endangered African forest elephants, among other wildlife. Bhutan and Gabon, like all developing countries, face the temptation to exploit their natural resources for short-term economic gain. But in Bhutan, development isn't just about accumulating ngultrum (the Bhutanese currency). Here, humans and the earth are equal partners in progress, bound to the same fate, choices, and trade-offs.

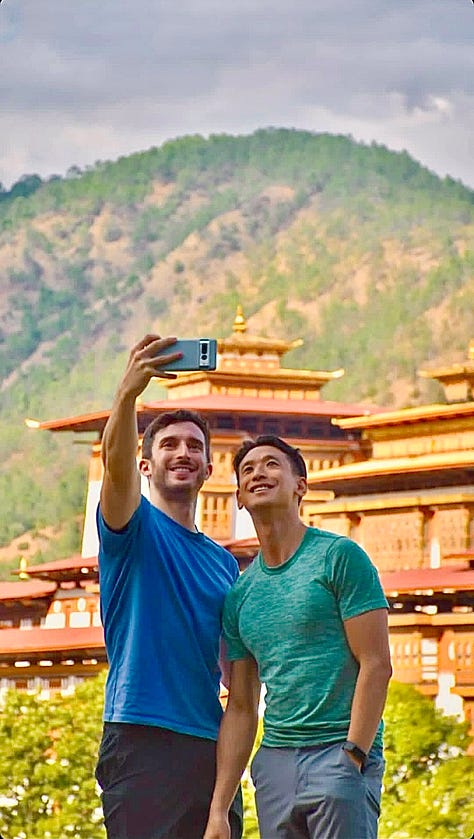

Beyond the environment, Bhutan is generally a country that does things its own way. For instance, this is the only country in the world without a single traffic light. Not even North Korea, a country I visited in 2015 (and documented as having the world's emptiest roads based on vehicles per capita), can claim that. The one intersection in Thimphu, the quaint Bhutanese capital, that ever gets busy enough to warrant traffic control is managed by a part-time, old-fashioned traffic cop. Even the Bhutanese post office is unlike any other. It's the only one in the world where it’s common to get legal, usable stamps with your own photo on them—a quirk of individuality in a highly collective society. My longtime travel companion and I ordered a sheet of stamps with our photo on it from Punakha Dzong, Bhutan’s largest fortress and temple, and the architectural highlight of our trip (and, we hear, of the country overall).

An old-fashioned crossing guard and personalized stamps might seem to have little connection to Bhutan's status as the world's most carbon-negative country. But they all stem from the same source—a country that makes deliberate choices, unencumbered by the homogenizing forces of globalization. It shows how societies that are collectivist at the micro-level can, if they remain true to themselves, be decidedly individualist on the macro world stage.

This kingdom was destined to be different due to a combination of factors: its geographic isolation within the world's tallest mountain range, the fact that it was never colonized, and a population small and homogenous enough (the vast majority Buddhist) to share a common vision. But destiny alone doesn’t fully explain Bhutan's à-la-carte approach to modernity. Its leadership has made intentional choices to manage the competitive pressures of the global economy.

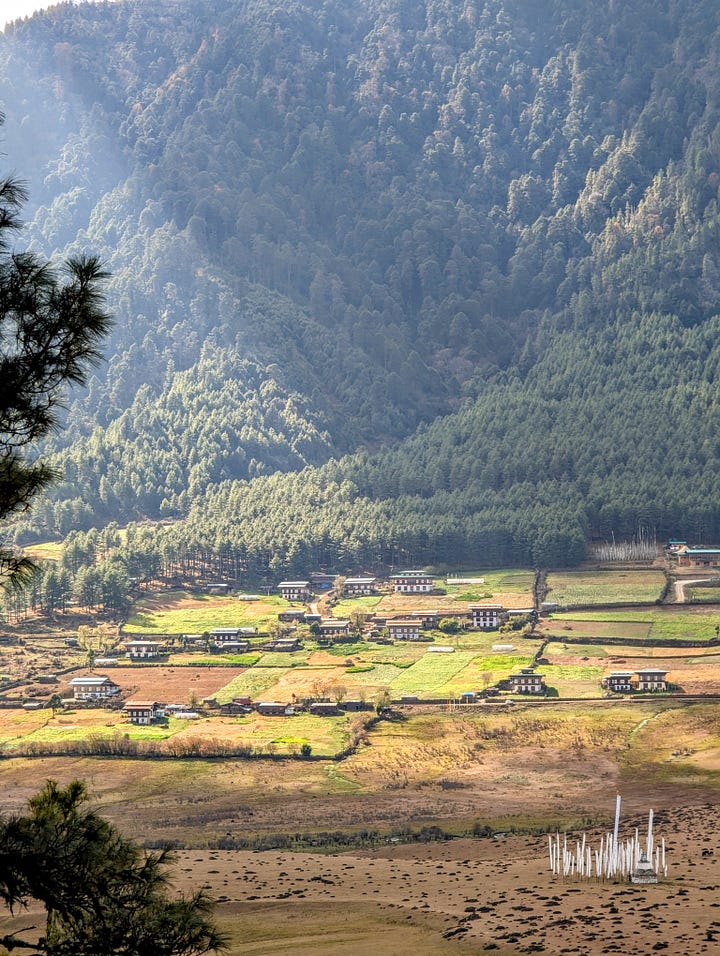

Little of what makes Bhutan unique, especially its environmental record, is accidental. The Bhutanese constitution mandates that at least 60 percent of its land must remain forested forever, a commitment to conservation and carbon sequestration of unmatched scale. My itinerary included daily hikes through the pristine forests that blanket over 70 percent of the country. These forests act as a giant carbon sink, absorbing millions of tons of CO2 each year.

Stepping into a postcard. Endless rice paddies of Punakha Valley sculpted by generations of farmers.

The good, bad, and ugly of globalization have infiltrated almost every corner of the world. I learned this when I saw my barber's son in North Korea shyly thumbing through a cartoon Lion King book in a country that supposedly has zero exposure to the outside world. I was also surprised to see how globalization persisted in Syria, even after George Bush labeled it part of the "axis of evil." Despite the Assad regime's proud rejection of Western influence, Kentucky Fried Chicken—a quintessential symbol of American culture—managed to operate for over two and a half years into the civil war. It was one of the very last foreign businesses to shut down (you can read more about this in my article in The Atlantic). In yet another example, after arriving in Socotra, Yemen, one of the most isolated islands on earth, I was picked up in a Jeep blasting "Smack That" by the Senegalese-American rapper Akon. Consumerism is pervasive, but when it comes to environmental protection, Bhutan has tamed it—redefining the paradigm for how developing countries approach industrialization.

Life in Bhutan moves at a gentler pace, in tune with the rhythms of nature. Farmers tend their fields with traditional techniques, forgoing pesticides in favor of organic methods that have sustained them for generations. Rushing rivers fed by glacial melt generate enough hydropower for Bhutan to export, mainly to India, bringing in revenue without environmental harm. In 2021 alone, Bhutan exported over 80 percent of the hydroelectricity it generated, helping neighboring nations reduce their own emissions.

Joining Bhutanese farmers in the age-old tradition of harvesting rice by hand, together.

Bhutan's embrace of hydroelectricity extends even to its spiritual life. Hiking past prayer wheels that turned, not by hand, but by the power of rushing rivers, I couldn't help but think: this is akin to the earth itself praying. The wind in Bhutan also prays. The Bhutanese say that the multicolored prayer flags, which ripple in even the most remote regions of the country, are equivalent to human windpipes reciting mantras.

In Bhutan, even the earth seems to pray. Hydroelectric prayer wheels, powered by the flow of water, spin endlessly.

Prayer flags ripple in the wind, their movement equivalent to the prayers of humans.

Bhutan enshrines its environmentalism in its national philosophy of development, famously known as Gross National Happiness (GNH). This measure of well-being isn’t just rooted in wealth and GDP, but also in spiritual, mental, and environmental health. Bhutan’s restraint toward and reverence for the natural world made me feel closer to the way things are supposed to be—a world in which development doesn’t mean sacrificing nature but living in concert with it. With its limited resources but boundless dedication, this small kingdom has achieved what many larger, wealthier nations have yet to accomplish.

Bhutan is living proof that sustainable progress is possible, that balance and prosperity can coexist, and that true wealth lies not in the exploitation of resources but in their preservation. By standing by its values in a world that has largely succumbed to consumerism, Bhutan has redefined what prosperity itself means.