From Gori to Gulag: The Unassuming Childhood Home of the 20th Century’s Most Powerful Man

The humble beginnings of the man who ruled one-sixth of the planet with a three decades-long iron grip: Joseph Stalin

📍Gori, Georgia (country)

The quaint Georgian city of Gori is an unassuming birthplace for one of the 20th century's most powerful figures: Joseph Stalin. From this humble town, in an even humbler house, emerged a man who would come to dominate one-sixth of the world’s landmass, ruling an empire that spanned two continents and hundreds of millions of people. For over three decades — two years longer than Mao, and 17 more than Hitler — Stalin held indomitable power that irrevocably changed the course of history.

And it all began here, in the simple, almost straggly, childhood home of Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili, later known as Joseph Stalin. It is hard to fathom that such an ordinary place could rear the man who would rise to lead the Soviet Union, an empire larger than any other in modern history.

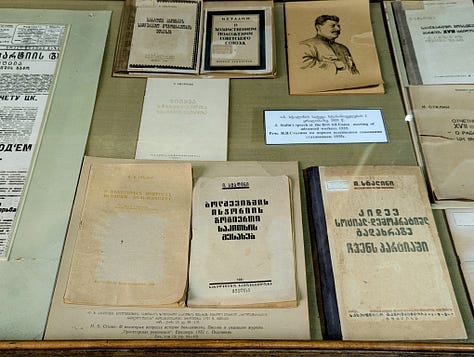

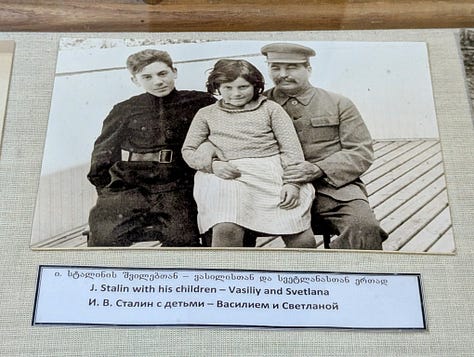

Stalin's early life was far from what it later became. The museum’s artifacts — an old school notebook, a worn pair of shoes, photographs of a boy who, at first glance, appeared to be just another child — made it difficult to reconcile his youth in Gori with his gory rule that followed. Here, Stalin is portrayed as a man of the people, not as one who discarded people (some 20 million of them) with merciless indifference.

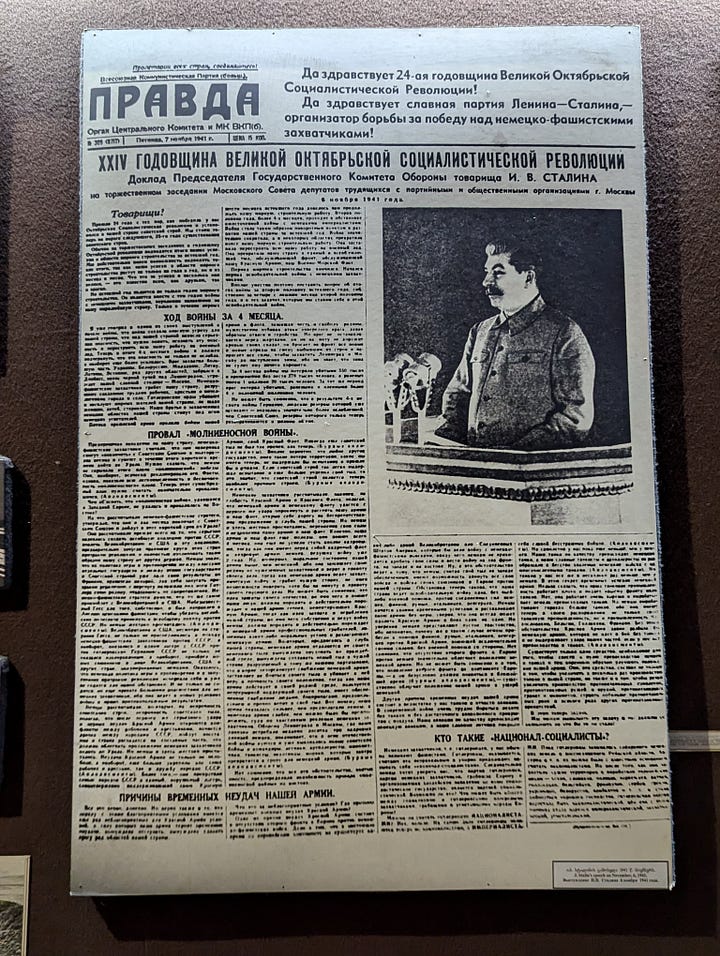

The museum exhibits the chronology of Stalin’s rise and the extent of his reign over the 15 republics of the Soviet Union, from the icy reaches of Siberia to the shores of the Black Sea. Stalin’s portrayal is curiously selective, if not downright warped, evading almost any reference to the Great Terror, the political purge that left millions imprisoned, executed, or banished to the Gulags. The focus is squarely on Stalin’s personal life, military strategies, and political accomplishments, including rapid industrialization through sequential Five-Year Plans that transformed the Soviet Union into a superpower. Propaganda posters line the walls, depicting the now fallen empire that was once in the throes of “progress” — whether through the construction of colossal factories or the triumph of the Red Army in World War II.

This celebratory narrative jolted me with dissonance and with the deafening absence of the millions of lives lost during Stalin’s 29-year rule. The museum raises the question of how legacies are to be celebrated or reckoned with, and shines a light on the choices that we make in remembering history. Here, beside Stalin’s home, the choice is clear: a legacy of fame, rather than infamy, for Gori’s most famous son.

Outside the museum, Gori residents are more nuanced when asked about Stalin. "He was clearly a genius," many say, "but we wish he had used that genius for good." The museum makes that genius clear in a parade of Stalin’s personal belongings: his iconic felt hat, his favorite smoking pipe, and his meticulously preserved railway carriage used for traveling to high-stakes meetings with world leaders. These artifacts depict a leader who built relationships on the world stage to expand his influence, feeding into the Soviet psyche’s and the Cold War’s competitive dynamics. But only the use, and not the abuse, of his genius is on display.

Leaving Gori, I found myself grappling with the enigma of how a child born in this once obscure backwater of the Russian Empire could leave such a monumental legacy. Gori is a humble town with an outsized role in history, seemingly unburdened by the complexities of its controversial legacy. The Stalin Museum itself flattens that complexity in its own way, rolling out a literal red carpet to a life-size marble statue of the autocrat at the entry. Yet, amidst its selective storytelling, the museum makes a decisive point: Power can emerge from the most unassuming places, and its roots can be as inconspicuous as a wooden house in a quiet Georgian town.

Very interesting. Easy to read and learn!

Genghis Kahn could be added to the list having ruthlessly ruled for 21 years.