The Jewish Legacy in Castro's Cuba: The Only Kosher & Private Butcher Shop in Havana

In communist Cuba, where atheism reigns, a kosher butcher shop serves as a surprising beacon of religious tolerance and tradition.

📍 Havana, Cuba

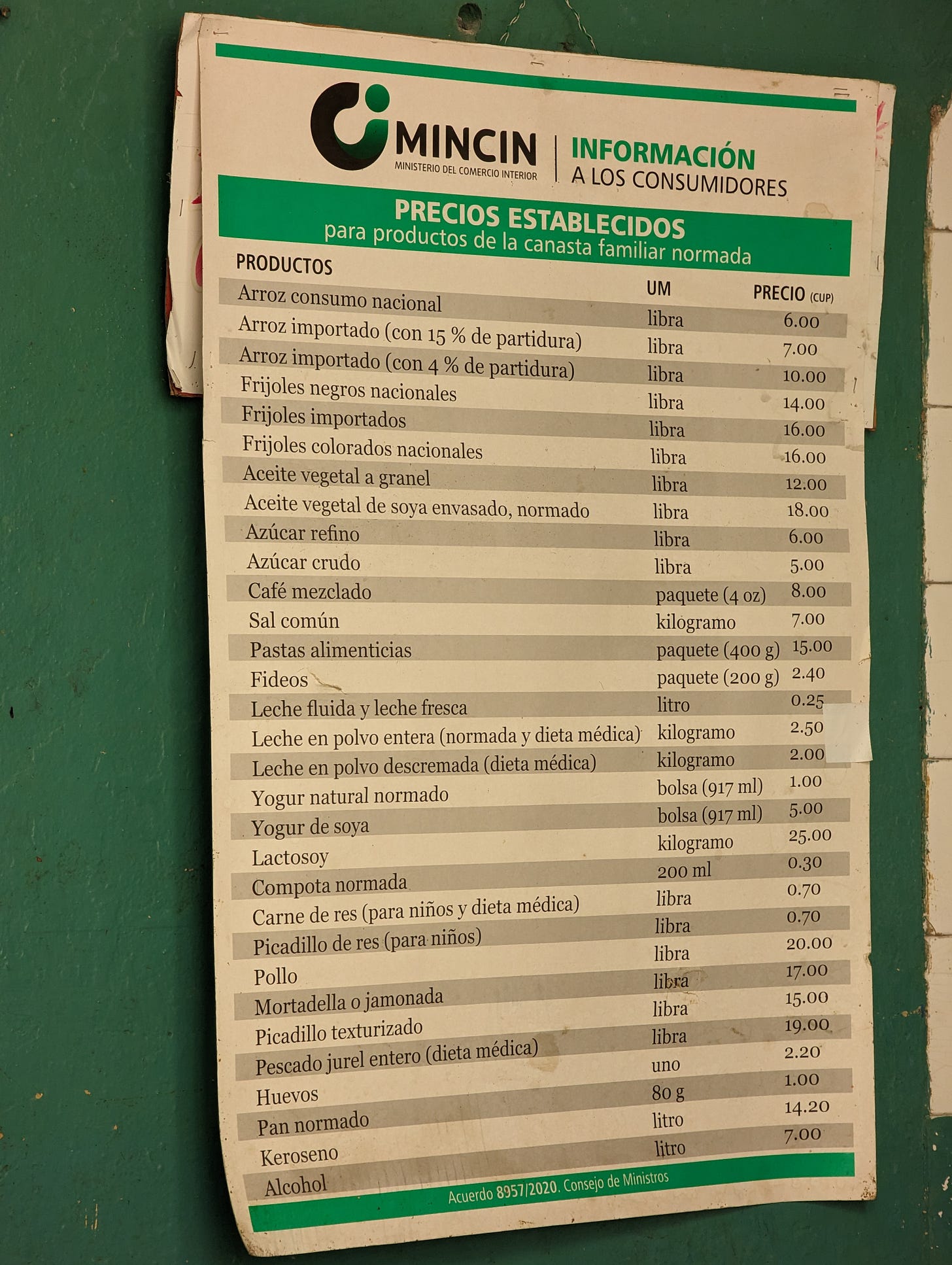

In a country where atheism is the official ideology, a lone butcher shop stands as an unlikely testament to religious tolerance. La Venedora, Cuba's only kosher butcher, is also the island's sole privately-owned bodega – a depot where people in this communist country pick up their rations. The butcher shop's existence speaks to the unique status carved out by Havana's Jewish community within Fidel Castro's Cuba.

The roots of the exception made for La Venedora by communist revolutionaries are deeply intertwined with the Cuban Revolution itself. Polish-Jewish figures like Fabio Grobart (1905-1995), Manuel (Stolik) Novigrod (1914-1989), and Enrique Oltuski (born 1930) played integral roles in the 26th of July Movement, the revolutionary group led by Fidel Castro that spearheaded the overthrow of Batista's government in Cuba. While Grobart and Novigrod were later purged from the party, their initial standing, along with Castro's pragmatic approach to preempting potential dissent, afforded the Jewish community a degree of accommodation for their religious practices.

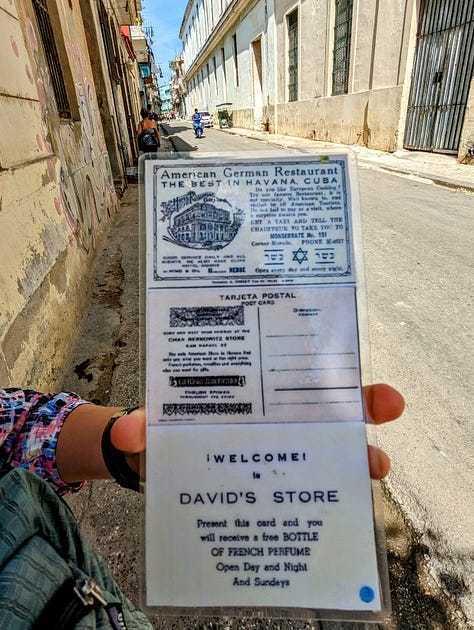

This tolerance became particularly valuable in a country where meat of any kind is hard to find – and not just for Jewish Cubans (often referred to as “Jewbans”). Non-Jewish Cubans, craving a taste of scarce meat, would seek connections with the “turcos” (“Turks”, referring to Sephardic Jews) or “polacos” (“Poles”, referring to Ashkenazi Jews) in hopes of black market access to La Venedora. Established in 1968 by Abraham and Sara Benchimol, the kosher butchery has been carried on as a family tradition by Sara and her children since Abraham's passing in 1992. It stands as the only option for those seeking to observe Jewish dietary traditions in the face of scarcity.

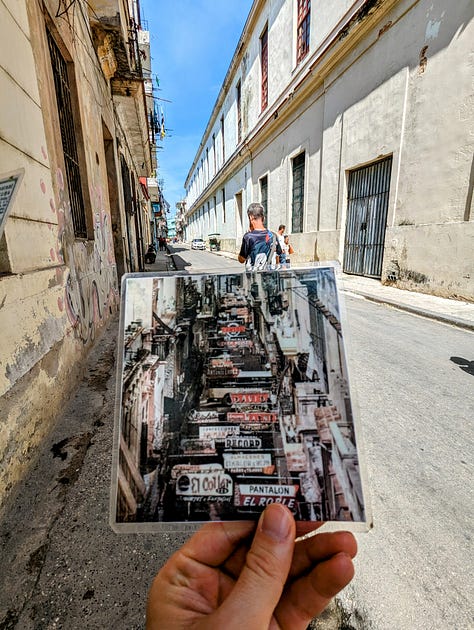

However, religious accommodation had its limits in Castro's Cuba. La Flor de Berlin, a once-thriving Ashkenazi bakery, now functions as a ration distribution center. Julio Lobo, Cuba's wealthiest man before the Revolution and a Sephardic Jew, built a grand sugar warehouse that now lies vacant in Central Havana. This iconic warehouse is undergoing renovations to house students from the developing world. Moishe Pipik, the kosher restaurant, and Chevet Ahim, once a vibrant synagogue, have fallen into disrepair, now tenement housing bearing only whispers of their history: a Star of David lamp here, a weathered Jewish fresco there. Economic hardship has driven over 90 percent of Cuba's Jewish community into exile.

Yet, even during this period of Jewish flight, the community experienced some gestures of religious tolerance. In the 1990s, during the celebration of Hanukkah, Castro himself paid a visit to Beth Shalom, Cuba's largest operational synagogue. There, he asked the community about the meaning of the holiday. Seeking to bridge the gulf between the community and the leader's inherently secular ideals, a member of the synagogue framed the holiday as “the Jewish Revolution,” invoking the shared language of struggle and sacrifice so central to the communist narrative.

The Jewish presence in Cuba extends back centuries, with some scholars even theorizing that Christopher Columbus himself had Jewish ancestry. La Giraldilla, Havana's feminine emblem akin to the Statue of Liberty, is said to have originated as a Sephardic Jewish woman. However, she became a "converso" after being forced to convert during the Inquisition. Today, she symbolically graces countless bottles of Havana Club rum – her religious origins largely unknown to the public.

La Venedora embodies an improbable irony: a kosher butcher shop thriving in the heart of a communist revolution. It speaks to Castro's pragmatism, his recognition of the Jewish community's historical significance, and his shrewd calculation that tolerance was a smaller price to pay than conflict. And in the end, perhaps La Venedora reveals something universal—the stubborn persistence of faith, even in the face of the most rigid ideologies.