The World's Largest Pyramid Isn't in Egypt, but in the Americas' Oldest City

The Great Pyramid of Cholula, Mexico is a layer cake of history whose pinnacle is no longer a Mesoamerican stairway to the heavens, but a Spanish colonial church

📍 Cholula, Puebla, Mexico

Most people instantly picture Egypt when they think of pyramids—the iconic Pyramids of Giza, perfect triangles rising from the Sahara Desert. But surprisingly, the largest pyramid ever built isn't in Egypt; it's hidden in plain sight in the central Mexican state of Puebla. The Great Pyramid of Cholula is a layer cake of history, with its ancient Mesoamerican base and a Spanish colonial church built right on top.

The world’s largest pyramid is a living capsule of Mexican history, with Spanish colonization and indigenous civilization intertwined within its form. Standing at its base, gazing up at the church of Nuestra Señora de los Remedios perched atop the ancient ruins, I was awed by the layers of history converging in Cholula, the oldest continuously inhabited city in the Americas, dating back to the second century B.C.

Few sites in the world can encapsulate an entire country's history as Cholula does. Perhaps Istanbul's Hagia Sophia, with its transformation from Byzantine church to museum and now a functioning mosque, comes close to being a digest of Turkish history. But Cholula's uniqueness lies in its simultaneous existence as both a Spanish colonial church and a relic of pre-Hispanic civilization. This monument has seen it all: civilizations rise and crumble, gods of both the old and new worlds come and go, and the forging of Mexico’s unique mestizo identity.

Cholula defied my expectations of a classic triangular pyramid. Instead, it appeared as a sprawling, grassy hill, its original form obscured by centuries of untamed vegetation. Abandoned long ago, nature had crept in to reclaim the pyramid. Only upon closer exploration could I discern the outlines of tunnels and chambers beneath the surface—remnants of a pre-Hispanic center of spiritual and political power.

Built over centuries by the diverse cultures that inhabited the Puebla region—primarily the Olmeca-Xicallanca and the later Toltecs—the Great Pyramid of Cholula is a collage of overlapping layers, each woven into the monument as new rulers rose and fell, reshaping it in their own image. Originally a sacred sanctuary dedicated to Quetzalcoatl, the feathered serpent god, its pinnacle was designed to pierce the heavens, providing a pathway for people to commune with higher powers.

The pyramid's sheer size is staggering: it sprawls across 45 acres, nearly double the footprint of Egypt's Great Pyramid of Giza. Yet, its height—a mere 66 meters (217 feet)—is dwarfed by Giza's towering 146 meters (481 feet). This emphasis on volume over height speaks to the pyramid's purpose: this colossal structure was designed not as a tomb for ostentatious Pharaohs, but as a living space for the common people to engage in rituals and sacrifices.

But as monumental as Cholula's pyramid is, what captivated me most wasn't merely its size—it was the church perched atop it. Nuestra Señora de los Remedios crowns the pyramid like a Spanish exclamation point on a sentence written in indigenous Nahuatl. Built by the conquistadors in the early 1600s, the church's placement atop the pyramid was a deliberate act. The Spanish, in their mission to extinguish indigenous beliefs and impose Christianity, saw this as a symbolic conquest: the new god, both physically and spiritually, on top of the old.

Before the violence of colonization shattered the Americas, the pyramid served as a stairway to the heavens, a place where gods and mortals met. Now, a church stands in its place, recasting those heavens and replacing the indigenous gods with a new deity. The pyramid is now merely a pedestal for this church. Yet, even in this attempted erasure of culture, a glimmer of the site's pre-Hispanic soul persists: the Virgin of Guadalupe within the church is not depicted with European features, but instead has dark skin—a blend of the indigenous and the conqueror.

One of the most perplexing aspects of pyramids, whether in Egypt, Mesoamerica, or elsewhere, is how different civilizations built them across the globe, often in remarkably similar forms—despite having no contact with each other. The Great Pyramid of Cholula in Mexico, the Great Pyramid of Giza in Egypt, the ziggurats of Mesopotamia, and the stepped pyramids of Central America all share a basic geometric form, yet were built independently, thousands of miles apart, by peoples who likely had no way of communicating or exchanging ideas.

This phenomenon has long fascinated me along with true historians, archaeologists, and anthropologists. Theories abound, suggesting that pyramids arose out of a common need for monumental structures that could bridge the earthly and the divine. Architecturally, their wide base is inherently stable and provides support for those heavenly heights. What unites these coincidental pyramids is a universal human longing to connect with a higher power (and, of course, their leaders’ desire to leave behind a monumental legacy).

Departing Cholula, I carried with me a profound sense of the interconnectedness of humanity. We share a common desire to reach for the heavens, to leave our mark on the world, and to connect with something larger than ourselves.

🕹️ Travel tip: For a truly magical experience, time your visit to the Pyramid of Cholula for sunset. As the sun dips below the horizon, the pyramid is bathed in a golden glow, creating a breathtaking spectacle. But the real showstopper? The stunning silhouette of Popocatépetl volcano in the backdrop. Try to visit on a weekend when the Iglesia de Nuestra Señora de los Remedios, the church perched atop the pyramid, is open to the public. The view from the top is simply stunning, offering panoramic vistas of the surrounding valley.

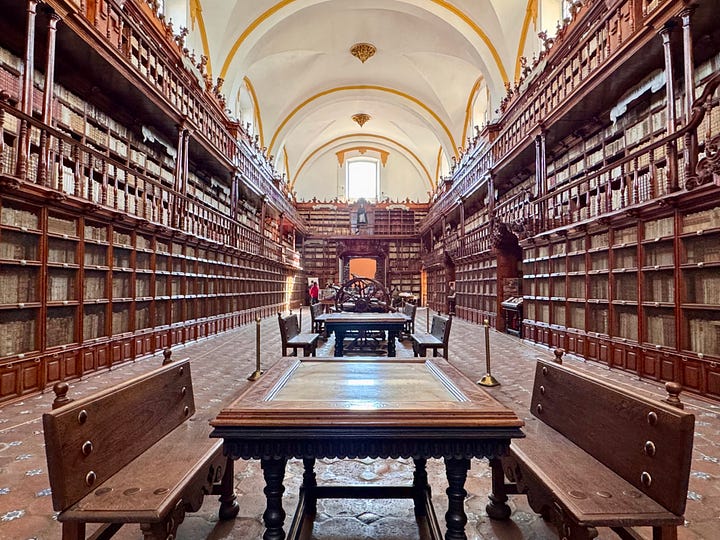

Don't miss the opportunity to explore the neighboring city of Puebla, a treasure trove of colonial architecture, delicious cuisine, and cultural gems. Puebla boasts several superlatives, including the Biblioteca Palafoxiana, the oldest public library in the Americas.