The Last Bastion of Jesus' Mother Tongue: Aramaic's Final Stand

The language of Jesus Christ is alive, and you won't find it where you expect. In a Syrian mountain village, the echoes of Aramaic cling to life, defying centuries of change and wounds of recent war.

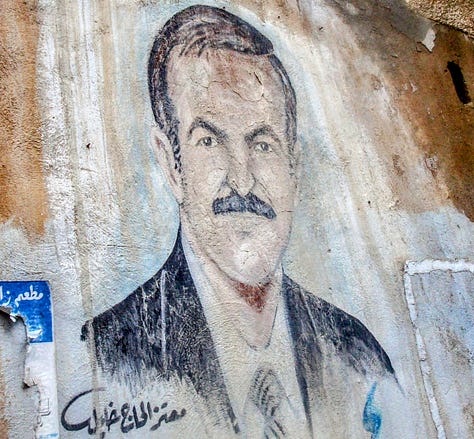

📍 Maaloula, Syria

The Aramaic language likely conjures dusty scrolls, biblical scholars parsing text in dimly lit libraries, or perhaps even Mel Gibson's "The Passion of the Christ." But this ancient language is alive – albeit unwell – in a Syrian mountain village called Maaloula. Caught between the scars of recent war and the echoes of a far more ancient world, Maaloula's two thousand-odd residents remain defiant. They are Aramaic's final guardians, its heartbeat persisting against the relentless march of the modern world.

Aramaic is the mother tongue of Jesus Christ, a language that once spanned empires only to seemingly vanish. In this defiant holdout, the final threads of a language that bore witness to among the most monumental chapters of human history remain.

Maaloula's story is one of improbable survival. Nestled in the mountains northeast of Damascus, its isolation shielded it from the linguistic tide of Arabic that swept over the rest of the Middle East following the Islamic conquests of the seventh century. When Arabic, the language of the Quran, became the new lingua franca, most abandoned their previous tongues, Aramaic among them. Yet, Maaloula's tight-knit Christian and Muslim communities clung to their ancestral language.

Modern roads and the ubiquity of Arabic media have chipped away at Maaloula's isolation, once key to the language's survival. Additionally, the village has faced two distinct migratory challenges: the allure of economic opportunities in larger cities and the brutal consequences of the Syrian civil war that have forced residents to flee repeated violence. As Maaloula tragically oscillated between the control of the Syrian government, opposition forces, and even an al-Qaeda affiliate, both its residents and the ancient linguistic heritage they uphold suffered devastating losses.

The world's last Aramaic speakers have weathered more than political strife. Their language has endured a battle over its very alphabet. Once written in a script closely resembling modern-day Hebrew – the language of Israel, Syria's bitter foe – Aramaic became a flashpoint for conspiracy and controversy. In 2007, the University of Damascus shuttered an institute founded just three years earlier in Maaloula to preserve the language. All signs bearing the Aramaic script vanished from the village. The institute eventually reopened with the promise of using the more distinct Syriac script, and the original script faded from public view.

A language can survive the loss of its original alphabet. For example, Atatürk's romanization of Turkish replaced Arabic characters, propelling the turn from the Ottoman Empire to secular modernity – met, of course, with resistance from traditionalists. Mid-15th century Korea saw a switch from complex Chinese characters to the easier, phonetic Hangul script in a push for widespread literacy. The Jews of Baghdad, once a third of the city, now vanished, preserved their distinct identity with Judeo-Arabic written in Hebrew script.

The language of Jesus, the vessel for millennia of history, clings to existence. It's one of hundreds of endangered languages slipping away unnoticed. Our hyperconnected world, both physically and online, has accelerated the pace of linguistic extinction. Every lost language takes with it a unique cultural heritage and record of lives lived. Maaloula serves as a bittersweet emblem of the preciousness and vulnerability of language – imperiled by globalization, war-driven displacement, and the drive for a common national tongue in schools and media.

Visiting Maaloula felt less like tourism and more like bearing witness. Hearing this relic of the ancient world spoken aloud is an awe-inspiring experience, one that lingers long after leaving this mountain village behind. It's a reminder that even as the world rushes forward, some echoes of the past stubbornly refuse to fade.

Who knew? What a story. What a storyteller.

I once had the extreme pleasure and satisfaction of being able to read a few snippets in Aramaic from the Dead Sea Scrolls in Jerusalem. It has many similarities to Hebrew.